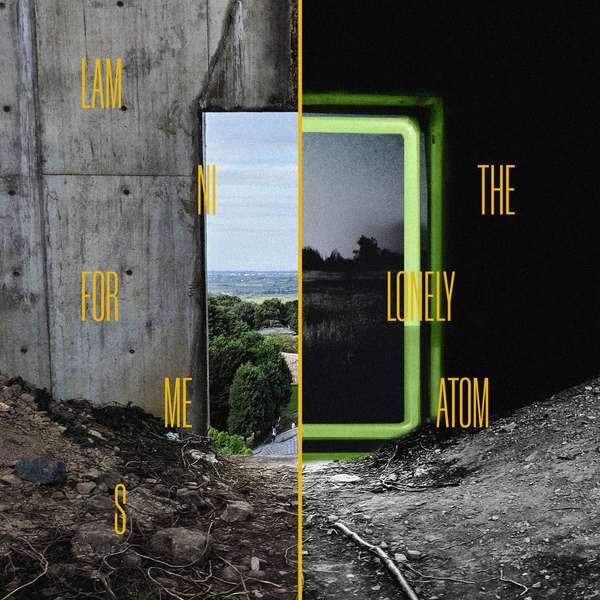

Ian Cory (Lamniformes)

SPB: Lamniformes is a one-man project, of sorts. Have you played in groups where you weren’t the primary songwriter and, if so, what did you like or not like about that dynamic?

Cory: I haven’t been the primary songwriter for any of the musical projects that I’ve worked on outside of Lamniformes. I am a drummer by trade and didn’t write full songs myself until college when I learned some basic piano and midi programing skills. This means that while playing in other bands the most I could contribute to the writing process were drum parts or suggestions for larger structural decisions. Sometimes I would give feedback about parts written by other band members, but I lacked the technical language to offer useful alternatives or additions to their work. By the time I had gained some fluency in that language, the projects that I found myself involved in didn’t call for additional songwriters, so these days I am rarely involved in songwriting decisions for any project other than Lamniformes.

Before I go any further in discussing the various pros and cons of these arrangements, I think it would be helpful to categorize the various arrangements I’ve worked in:

- Totalitarianism: These are projects where every musical decision is made by a single entity. There is no wiggle room or need for creative input. Sometimes in the case of musical theater or cover projects the creative decisions aren’t even made by the musicians playing the music. These are more likely than not paid gigs, and are best approached as a job rather than as personal expression.

- Songwriter authoritarianism: There is a single primary songwriter who has final say over any creative decision from songwriting to arranging, which may or may not involve suggestions from other bandmates. In recording setups, this would also put the songwriter in what is traditional the “producer” role. This is how Lamniformes operates.

- Arrangement democracy: The songwriting itself is controlled by a primary songwriter, but arrangement decisions (i.e. individual parts, instrumental, timbral, and dynamic choices) are fielded out to the other members of the band. The songwriter will likely still have final say, but will leave it up to the drummer to write drum parts, the bassist to write bass parts, etc.

- Songwriter confederacy: The classic Beatles set up where there are multiple primary songwriters in a project who bring in their own separate songs which can then be arranged in one of the previous methods described.

- Songwriter aristocracy: Some band members have democratic input over the songs, others do not and play the parts written by the “ruling class.” I’m pretty sure this is how Steely Dan worked.

- Band democracy: All band members have equal say in how songs are written. Very common in the early stages of a musician’s career and in amateur settings. Much rarer in “professional” contexts.

In my experience, categories 4 and 5 are very rare so I won’t talk about them at length.

Category 1 is very common for working musicians, but isn’t really talked about much in settings like this because they completely defy all independent music cultural conceptions of art being primarily a form of self-expression. Some people might find the idea of “clocking in” to play music that they don’t have any personal investment in soul crushing, but personally I’d take playing corny musical theater gigs over customer service any day.

Category 6 sounds great on paper, at least for a lefty like me. But while I’m all in favor of expanding democracy in matters of real world importance, like say in the workplace or government, when it comes to songwriting I’ve found full democracy to be self-sabotaging. There are three big problems with band democracy:

Time: Writing as a group requires every musician to be present in a rehearsal space, to be given a chance to offer their thoughts and suggestions for the structure of a song, and then to work out their parts in real time. In the time it takes a group of three or four musicians to reach a satisfactory compromise about one song, a single songwriter can potentially finish multiple songs. Realistically, time spent in the rehearsal studio is better spent rehearsing and not fussing over the details of an unfinished piece of music. This issue can be mitigated by members writing separately or having fewer members contributing to songwriting, which both quickly lead to less democratic arrangements that I described above.

Taste: Reaching a successful consensus about a song is only possible if the musicians involved have a shared vision of what they are trying to sound like. That isn’t a given in most bands. Conflicts of taste can slow down the songwriting process or kill a song before it even gets started. Now sometimes creative conflicts can result in interesting music, but more often than not it can lead to resentment and hurt feelings that can tear a band apart.

Talent: The bluntest way to put this is that sometimes a good musician can be an absolute shit songwriter. I say this as someone who was terrible at writing songs despite being good at drums until recently.

The purely democratic bands that I’ve played in were often very frustrating experiences, even when they resulted in some very fun music. More often than not, the problems caused by the “three t’s” made these bands untenable in the long run, or slowed production to such a crawl that the pace of adult life rendered them obsolete. I don’t want to write a band democracy off completely, but these days I can’t imagine finding the time and space in my life to make one work.

The fact of the matter is that some band members' time and efforts are better spent on tasks other than writing songs. Songwriting is a specialized skill, just like booking shows, accounting, designing merch, running social media, or audio engineering. In this respect, band democracy is better when implemented on the administrative level. From each according to their ability, etc.

Quick caveat: bands that write or perform in an improvisational style can cut through a lot of these problems. Your results may vary as to whether the results are worth listening to though.

All of this is to say that all of the projects I work in these days fall into categories 2 and 3, and I prefer it this way. Humeysha, Sharpless and Bellows are all authoritarian states where the songs are fully formed by the time I start playing them, although Zain, Jack and Oliver are each open to hearing my suggestions for the details of drum parts for live performance. Gabby’s World and Small Wonder are both arrangement democracies. Gabby and Henry aren’t very focused on rhythm in their songwriting, but both do have a clear idea of what they want their songs to sound like, so it’s my job to write drum parts that fit those ideas.

I find both of these categories fulfilling and productive in their own ways. Maybe I would feel differently if I didn’t have Lamniformes as an output for my own songwriting, but I think that even if I weren’t writing songs I would find it gratifying to help others bring their visions to life in whatever capacity they need from me.