Pioneering punk/post-punk band Wire should be no stranger to purveyors of fine taste in music. Throughout their storied career, they continue to release quality product while maintaining integrity, self-reliance and sustainable output. It is the opinion of many that Wire is one the most important and innovative bands in the history of British rock music and beyond. Wire has never been a band to remain stagnant and has always evolved and experimented with sound. Always reinventing themselves in an essence. I recently had the opportunity to talk to Colin Newman about his many projects and his direct involvement in them (also with collaboration with his wife Malka -- now known as The Selector!). Colin also elaborates on what helped shape his musical identity, living in the time of COVID, guitars, and how he has found the time to appreciate others' music again largely through his much loved and aligned radio show.

Direct links are posted below for those interested in checking out Colin’s and Malka’s radio show and any of his other projects.

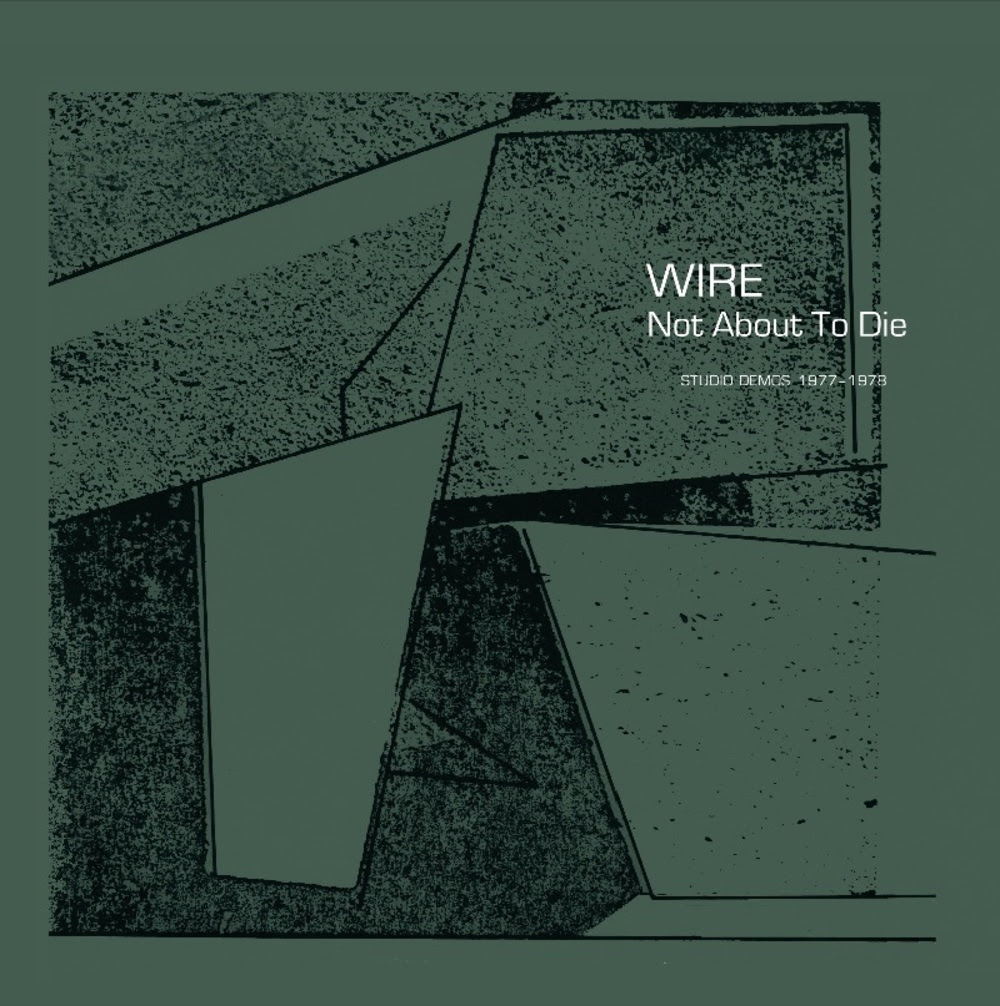

Scene Point Blank: What can you tell me about the latest release Not About To Die (Studio Demos 1977-1978) and how it came to fruition?

Colin Newman: Well, they were intended as demos, of course. However, I believe there was an EMI compilation in the 1990s that might have had a couple of songs on it but the majority never were released. The world was very different then. A band that signed to a major label had to prove themselves approximately every three months that they were worth the money so we had to demo everything we recorded. You just accepted it as that was something you were supposed to do. We were reasonably naive when we started. Now there were independent labels but no independent labels that were actually in a position to give you any money even if you sold records. There was no other alternative to the way that major labels had been doing it for a long while.

Scene Point Blank: Was that a common occurrence that music would get leaked within the company?

Colin Newman: It is a moot point and difficult to know. We demoed about 50 to 70 tracks over 3 years, so quite a bit. The people who put the original bootleg together picked what they thought was the most commercial selection of those songs. So the demo version was very different than the final recorded version of all the songs they chose and were changed radically.

We treated it as “ready-made”. If you are going to do something like that then don’t just do it for artistic reasons you can also make a point. We are saying, “We own this and we can do what we want with this.” It is a commentary on the music industry both then and now. By picking the most commercial tracks the original bootleggers were trying to make the most amount of money out of the bootleg. So they did that work already. It is the same tracklist in the same order only it is properly mastered. However the cover is a bit poshed up, but we have stolen their artwork concept back also!

Scene Point Blank: I believe it was Johnny Thunders' family who had released bootlegs under the title of Bootlegging the Bootleggers.

Colin Newman: Yes, I think this is part of the commentary of the past because this did exist. Bands signed to record labels wouldn’t see much in terms of income because their deals were not very good and they had advances that they had to recoup out of the sales. Most bands didn't do enough sales to recoup their advances. So the system was iniquitous plus on top of that, someone else would be bootlegging your material and putting the money straight away into their pocket. So it was like a double whammy. the situation now in the record industry has not become any less iniquitous. What is happening now is that so many catalogues have been aggregated into a smaller and smaller number of companies because lots of labels have gone bust or changed hands over the years and those companies have acquired those rights. They only have to pay the artist on the terms of the original contract.

If you look at the '60s and ‘70s contracts you are looking at artists getting very small percentages. So when it comes to streaming where the costs are minimal it means that those record companies are making huge amounts of money from that catalogue. Some of the bigger artists re-negotiated better deals and they are doing ok from it. But if you look at Spotify, some artists get 7 million plays however they are getting virtually nothing out of that. You can criticize the percentages shared by Spotify; however, in most cases they are paying the rights owners (labels) not the artists…

With Wire, we own the classic catalogue. We are in a highly enviable situation. I can make a commentary on that because I know what the Wire catalogue is earning. I can look at the streaming numbers on Spotify and compare that to someone who streams a lot more than us and extrapolate what their catalogue is earning. Some of those artists are complaining about not having any money.

Scene Point BIank: I read that Spotify said: if you want to make more money, release more music.

Colin Newman: It really isn't about Spotify. What Spotify pays could be better but it is the amount of money that is being shared by the record company that owns the rights that is the problem. The record companies are very happy that everyone is blaming Spotify.

Spotify is far from perfect. They are a large corporation. I wouldn't defend them on any level. but it isn't about them. They are just a means. If artists were getting a fair share of what Spotify is earning them some artists still wouldn't be making a lot merely because they don't get streamed enough. The only way to do that is to increase the monthly charges for users. If people expect that they are going to get all the music that has ever been released for 5 dollars a month. There are millions and millions of tracks on Spotify there are not that enough people subscribed to Spotify to cover the costs of paying out all those artists fairly at the current monthly charge. Plus there are several million tracks on Spotify that have had zero plays.

Scene Point Blank: So Wire was very smart about it right from the beginning.

Colin Newman: No, not really. Wire became smart, basically. It started with the label, swim ~, that I run with Malka. We have been going since the ‘90s. I learned how to run a record label in running swim ~ and then brought that to pinkflag. pinkflag has only been in existence since 2000 but, since then, we have a huge catalogue. We don't own everything. There are parts of the catalogue that we do not own and that we virtually earn no money from it. It is crazy. That is the reality for the rest of the world.

Scene Point Blank: I believe you have 17 releases out there.

Colin Newman: We might but I am not counting, haha. The last new Wire release was in 2020.

Scene Point Blank: How did Covid affect Wire and you as an individual?

Colin Newman: Oh, blimey, that is a big question! I have had three injections. I have personally had it and so has Malka, back in April 2022, like a lot of people that have not had it up until then. Still here to tell the tale.

2020 was an amazing year -- everything ground to a halt. I am not about to say anything highly original here but you re-evaluate everything on how life can be different.

I am in a very fortunate position that the Wire catalogue does earn money. It is not a life-changing amount of money. No one in Wire is considered rich. There are plenty of people in their sixities, seventies, and eighties that have to go out on the road in quite poor conditions with not-brilliant personal health so they can just pay their mortgages. Wire is not in that position; they can survive with what they are earning which is an amazing thing without actually doing anything.

Scene Point Blank: A lot of bands I have spoken to are in the unfortunate position of making their money off merchandising and touring.

Colin Newman: Yes, that is correct because they don't own their catalogue. If you own it you make money out of your catalogue. You have to be prepared to get your hands dirty by actually doing business. You can't just sell a few t-shirts and tour and then think the record company will just take care of the record. Yes, sure, the record company will take care of the record. However, even if they are good guys they have an office to run and people to employ, they have mouths to feed and costs involved with putting out records.

The whole industry of manufacturing vinyl is screwed because there are fewer and fewer plants, long delays and a shortage of vinyl. Us musicians are supposed to be leaders in creative thinking and we put our records out on vinyl, one of the most toxic products in the world! it is all an enormous mess that came crashing into sharp focus in 2020. You realize that when everything stops…oh, that is how the world is. I think this is before and after and in many ways the after is much more interesting than the before. I am a different person. I am actually in a very different place from where I was in 2019.

Scene Point Blank: I had been speaking to Paul Leary of the Butthole Surfers who stated he enjoyed isolating himself as he spent more time in his studio creating music, re-releasing some of his solo stuff and looking at remastering/re-releasing some of the Butthole Surfers stuff, etc. Some people took advantage of not having commitments and were able to spend time in their studio and create and work on projects.

Colin Newman: Yes, or spending the time living the moment just being. May 2020 where I am (in Brighton) was glorious, the weather was just amazing. It was warm and sunny. There were no aeroplanes in the sky, no cars on the road, and a full-blown spring. I could walk out in nature. I could walk up into the hills of Brighton and not see any houses and it was like it could be 1,000 years ago. There was nothing in front of you that would be any different 1,000 years ago. It was almost primal and I loved that.

Scene Point Blank: I can appreciate that. This is one reason I moved out of a large city (Toronto). I can look up at the sky and see the stars and no light pollution. I can see shooting stars and breathe fresh air. I also appreciate total quietness.

Colin Newman: If you are going to live in a bubble there are a lot worse places to be. Brighton is an amazing place when the sun is shining. It has a strong artistic community and is very walkable. We basically plugged into the city.

Malka and I now have a radio show which started in July 2020. It is broadcast on a local station (Slack City) and put on the internet as well.

The radio show is called “Swimming in Sound.” We broadcast once a week in real-time but are very lucky to be part of a huge archive called Totally Radio. All the shows have been archived. So you can hear all our past shows if you have the time to listen! We discourage record companies from sending us stuff -- we buy everything we play. We are highly principled. Since we are both musicians and a record company we know the game and we do not want to be beholden to anyone. We play and buy the things we like and hopefully, that is okay.

Scene Point Blank: Is it just newer music you play on your show?

Colin Newman: Mainly newer but definitely not all. Do you know the Jamaican term "the selector"?

You have different types of DJs… DJs who are good at the physical art of actually DJing. They can play one record after another without a clash of beats. Proper beat matching in a sense. DJs who can move a dance floor and there are DJs who have all the best tunes. The Jamaican name for that is The Selector and Malka happens to fall into that category. It was something we didn't know when we started the show. She has a way of finding and selecting music.

We didn't expect it to be like that but for the most part, we mainly play new music -- Music released over the last few years. We are discovering stuff all the time and it is very, very broad. It is curated by aesthetic not genre. We don't stick in any one place, we try and keep it as wide as humanly possible. We don't play music we don't like, ha.

Scene Point Blank: I can align with that as I only recently got back into writing and interviewing but I find myself, through that, discovering and going back into history to see who influenced whom. Essentially I am always talking about music. It is nice to find like-minded and open-minded people who appreciate music. I don't limit myself to one genre or style. I want to hear everything. Doing what I am doing has exposed me to stuff that I wouldn't have even known existed.

Colin Newman: It is a kind of food. The list of artists that we have discovered is incredibly long. Doing a show once a week for nearly 3 years at two hours in length is quite cathartic. It is an amazing thing and it has put us in touch with many different, interesting artists.

Malka and I also work together on something called Immersion. We have been doing it for a long time. However, during the last few years, we have had a collaborative event at a venue in Brighton. We make collaboration by creating music in our studio with a guest and we have to create a half hour of new music between us. and then we go and perform that live. So it is not just standing there making stuff up. They are pieces that we have written together with our collaborators. The project is called Nanocluster. We have taken the tracks that we have worked on over the four collaborations and put them out on a double 10” (Nanocluster vol. 1). It is something that I am incredibly proud of.

Now in 2023 we are well into the 2nd cycle of Nanocluster and have completed the first collaborative performance with Thor Harris at SXSW in March. It was the first but definitely not the last Nanocluster we plan outside of Brighton.

Scene Point Blank: What and who influenced you originally?

Colin Newman: That is very age-related. When I was young, between 7-to-10 years old, I had extremely strong views on music to the extent that music I didn't like made me feel ill. I didn't like any music from the ‘50s. It was all black and white and horrible. I didn't like rock ‘n’ roll.

I loved the Beatles and I loved Motown. I thought that the music released by The Beatles and the music on Motown were absolutely perfect. I thought there were other people making music that could probably do with a bit of help and I was there to help. It was the arrogance of youth that entered the ‘70s with an encyclopaedic knowledge of the ‘60s. I was that nerdy kid who knew every band. Certainly, Small Faces. However, was not my generation; that was the generation before. I was a kid in the '60s. If you talk to anyone who was a grown-up in the ‘60s they would cite the Small Faces as a very important influence. (Well, that being said, the British did anyways.) Also The Move. Everyone I know who was a certain age and who saw them live would say they were absolutely the best live band. They were doing what the Stones and The Who were doing later, first. They were wilder, madder and crazier and more in your face. Going through the early ‘70s to whatever was fashionable.

I started reading the NME when I was 8. I would read it cover to cover and do all the crosswords. I was completely obsessed. So whatever was on the cover of the NME I was into. When the Joni Mitchell, Crosby Stills and Nash thing hit I was well into that; I was very big into Neil Young, Bowie and glam to a certain extent. Bowie is great! The Sweet is not so good. Early prog. Late prog was not so interesting to me.

Punk rock when it started, but not for long. Very short, actually. I think even going through into the mid-to-late’ 70s I had a pretty good idea of what had gone on in the history of music and this was back in the day when there wasn't an actual timeline.

The ‘60s were kind of absurd. Bands that were all mods one week were all hippies the next week because the fashion had changed. It was just how it was. It wasn't taken too deeply.

Scene Point Blank: It was also a time when you discovered music by word of mouth or, as you have stated, in magazines. It wasn't like today where you can go online to Spotify for example and download the whole discography of Sir Lord Baltimore or Hawkwind.

Colin Newman: When I was a kid I would go down to the town centre and go around to the record shops listening to sides of the LPs in the booths. That is how you heard music. Well, that and John Peel. That was it. Daytime radio wasn't playing this type of stuff, especially when you got to the early ‘70s and you started to get album artists. This wasn't being played on National Radio. There wasn't anywhere you could hear it so you could read about it. It would be on the front cover of the NME and you wouldn't hear it on the radio, which was completely weird.

Radio, however, was important. I have a great fondness for radio. Radio was hugely important to Britain in the ‘60s. For a lot of strange reasons the BBC, when I was a kid, had only four hours of pop music programming a day. That was it. They played such a broad selection of stuff so British kids grew up hearing beat groups in Britain and Motown and soul acts from American and Jamaican acts...That was just pop. It wasn't divided up the way it was in America and that was because the people that had the power didn't take any of it seriously. It was just all pop: this is what the kids want let's just give them that. So it was for cynical reasons but, obviously, there were some enlightened people in there thinking we can play this and we can play that.

I feel like this was a very important influence on me.

Scene Point Blank: Did you not also have pirate radio in Britain?

Colin Newman: Yes, but the problem with Pirate Radio was your signal was not continuous. It was your only choice outside of Radio 1 which was the national pop station. Radio 1 didn't launch until 1967. Up to that point if you wanted to hear pop music outside of the hours that BBC was broadcasting it, you would have to listen to Pirate Radio.

Pirate Radio signals were so bad or you listened to Radio Luxemburg which was very loud but would gradually fade in the cycle of about three minutes. It was a struggle to hear popular music at that time. in an era when Britain kind of defined it for the world.

There was another generation of pirate radio stations in big urban centres in the ‘90s and 2000s and they were the people who created entirely all the waves of dance music. It all came from pirate radio because there was this whole pile of music that was not being played on mainstream radio and that was mainly black artists and there was a huge market for that music so many people wanted to hear that music. It took off massively and, in the end, some stations were getting licences and then moving very mainstream.

Overall it was a fantastic definitive moment of British radio. I believe some of those stations still exist on the internet.

Scene Point Blank: I don't believe, in Canada, we ever had an equivalent of a John Peel championing The Undertones. We had radio personalities but no one of that calibre that I am familiar with. I grew up in small towns and listening to stations that peddled classic radio. Britain was very lucky to have Peel.

Colin Newman: Yes, we were lucky. I am not sure about Canada. Well, I know that Canada is more liberal than the USA but it was so divided by race. Radio was basically racist in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Yes, you mentioned classic rock radio. How many black artists were they playing on those stations? Not many I would say.

It is shocking when you think of it...but then you see what the result of that is. The first Jamaican record I ever heard was My Boy Lollipop by Millie Small. I was very little when I first heard it and I thought it was just great pop music. I didn't know anything about it or what it was at the time. It was different-sounding pop music and I thought it was very cool.

Scene Point Blank: I can align with that as well. The first concert my aunt brought me to was Peter Tosh. I was in I believe Grade 8. Everybody was standing on their chairs and Peter came out with a joint the size of my arm saying “Haile Selassie” and everybody in that whole auditorium lit up. I was amazed that many people smoked marijuana and I was pretty sure I was high off the air as a young kid. To me, the music made me feel good and I couldn't care less that it wasn't played on the radio and I still like Peter Tosh to this day. It was all about being exposed to music and different music, at that. I think I was the only kid that wore a Brian Eno shirt or listened to Klaus Nomi, for example.