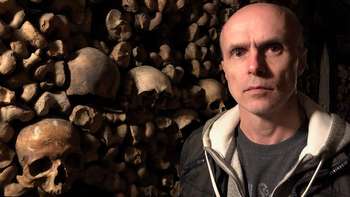

Matt Goud apologizes for being late and offers to buy me a coffee. He says that he's really grateful I would take the time to do an interview. When I explain that I'm a fan of his work and have been following his music for the past few years, he seems genuinely touched. As I set up my tape recorder and we continue to make small talk, I can't help thinking to myself how overwhelmingly nice he is. Matt's sincere, friendly, and welcoming, These aren't the kind of qualities I'd usually attribute to a man about to play a sold out show in a dimly lit tavern but, then again, maybe that's the reason why his music is so good.

Matt Goud, who plays under the moniker of Northcote, is a former punk rocker who's abandoned his distortion pedals and taken up a singer-songwriter approach to music. That's a common theme among a lot of Matt's contemporaries, he's played on multiple legs of Chuck Reagan's Revival Tour and is currently co-headlining the Devour America tour with Dave Hause, but Northcote moves far beyond the idea of a punk with an acoustic guitar. The latest album, a self-titled record released in 2013, has drawn favourable comparisons to The Weakerthans and Hey Rosetta!

I went into my interview with Matt hoping to chronicle his small town upbringing—he grew up in a town of about 1000 people in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan—to his success in bands, first with the Christian post-hardcore act Means and later with Northcote. What the conversation ended up being was an honest and difficult chat about the power of music and what it is to grow up.

Scene Point Blank: How did a kid from the Canadian prairies first discover punk rock?

Matt Goud: Well, my first music experiences as a kid were country and church music. I was raised similar to the Mennonites. I didn't grow up with The Beatles or The Rolling Stones, because my parents didn't listen to any of that. Later in life some friends had some punk CDs at camp and my brother got a Smashing Pumpkins cassette. The sadness one?

Scene Point Blank: Melancholy and the Infinite Sadness.

Matt Goud: Yeah. I remember thinking that was so cool. My home town is about a thousand people. So there were only a handful of kids who ever knew about bands like AFI or Hot Water Music. That's my generation of punk. One of the first shows I ever went to was the Warped Tour when I was in grade 10. We piled in a buddy’s vehicle and drove all the way to Calgary. It was amazing.

Scene Point Blank: Being from such a small town, did your musical tastes ever reach a point of contention with your peers or your parents?

Matt Goud: Not really. I had some shirts with upside down flags and stuff that they didn't like but…I was always a well adjusted kid. I'm a late bloomer in a lot of ways. I was a pretty devout, sheltered, kind of kid until I was about 20. I wasn't allowed to go to school dances, or I'd get in trouble if I ever had a beer or whatever, but they didn't bother me too much about music.

Scene Point Blank: Doing research for this interview I was trying to find the link between your upbringing and the success you've had in music. Your former post-hardcore band Means was considered a Christian group. The music you're making now doesn't seem to have a religious tone, and I know it was a huge part of your upbringing, but do you still consider yourself a Christian?

Matt Goud: I think it's a big part of who I am, but I don't really identify with that world view anymore. That's the short answer.

Scene Point Blank: I think it's difficult to be a religious person within the music world sometimes. The backlash that Thrice withstood was pretty outstanding. Did you ever experience any problems?

Matt Goud: I don't know. I was training to become a minister for awhile but I quit doing that. I was got frustrated. When I was playing in Means I got frustrated. In Canada we got to play with everybody. We got to tour with Misery Signals and Shai Hulud. We were in the mix. But every time we went down to the States we would only get booked to play certain events. We got put on tour with a lot of Christian bands that I wasn't comfortable standing beside. They would say things that weren't really representative of my conviction…but that wasn't what turned me. There was a lot of personal study and conversations between friends where we decided that…I don't know.

Scene Point Blank: Did that change had anything to do with punk?

Matt Goud: No. I was still a devout person for many years after I discovered the music. I just happened to be listening to bands like Good Riddance. I learned a lot though. I remember the band D.B.S from Vancouver had a song called “Immovable Stones” which was about homosexuality. I had never met a gay person and I didn't know anything about it. I was learning about other people through the music. I was a small town guy. I'm a small town guy still. But I got to learn about things like becoming a vegetarian or political ideas. I don't know if I would have thought about that stuff without music, so I had those worlds colliding: my Bible upbringing and my social awareness.

Scene Point Blank: Around the time I stopped going to my church's youth group was around the same time I started going to concerts.

Matt Goud: Music can kind of do what I'm missing from being a Christian. It's a lot to think about.

Scene Point Blank: It's a tough topic. I didn't mean to blindside you.

Matt Goud: No, it's fine. I think that music and art in general makes you feel less alone in life. When you're seeing a band you like, or a play, or something you get pulled into human kind or whatever. That kind of thing is a mystery to me…but I think you can get that kind of thing through art. You don't have to put up with the things about religion which may not help anyone.

"I think that music and art in general makes you feel less alone in life."

Scene Point Blank: Was Northcote a byproduct of Means breaking up or was this something you always wanted to pursue?

Scene Point Blank: Was Northcote a byproduct of Means breaking up or was this something you always wanted to pursue?

Matt Goud: I wanted to do it. I was trying to do it all along. I was playing in cafes for free and for friends. I even ended up playing a State Fair—I don't know what we'd call that here in Canada—I ended up playing a fair with Silverstein. I had like five songs and it was well…[Laughs]. When the band broke up I needed a new form of expression. I wanted to try songwriting like this and see what that could mean.

Scene Point Blank: Do you feel as though you're able to express yourself more with Northcote than you did in a band setting?

Matt Goud: Not necessarily. Hardcore music was very expressive for me. It's very physical and there is something to that. But it's just the way I've grown, this is what I want to do. I guess I could still play hardcore. I've thought about it. There are times when I want to do it but, when it comes down to it, what I want to devote my time to is Northcote. This is what I do every day.

Scene Point Blank: This is a question that gets asked a lot, but why do you think that so many punk or hardcore people end up making the switch to a mellower type of music?

Matt Goud: I get asked that a lot and I'm not sure what the answer is. I think it's the punk ethic where your main goal with the band is to connect with the audience. You're not trying to get on the radio or get sponsored. You don't give a shit about that stuff. All you care about is people watching you sing your songs. I think when you're alone on stage with your guitar you get a sense of survival. It's that same scary position. If I had gone from hardcore to being a concert piano player—which would actually be amazing—it might be different. But all the guys I know who are making music that way are still aching for that connection with the audience. Some of us are quieter, yeah, but someone like Tim Barry, he's on stage just surviving. He's very captivating and physical and it's all just him. I think that challenge or survival on stage is what it is that remains the same.

Scene Point Blank: How so?

Matt Goud: It's the drive. If you look at it punk/hardcore people are really successful in a lot of other things too. Business. Or you hear of these punks getting PHDs or running things. I'm not sure what it teaches everyone but it's a certain ethic

Scene Point Blank: Is that what drives you?

Matt Goud: I think I just want to connect.