Scene Point Blank: I have been reading a few books lately and a name has come up in a few of them: Jack Rabid.

I did a few articles for him. I wrote him out of the blue with next to no experience and he took me on and helped me get going, which was very cool of him. Anyways, Jack Rabid and Doug Holland from Kraut both welcomed you and the band to NYC with open arms?

Mike Magrann: Oh, yes, for sure they would welcome you to their tiny little walk up. This past November I was doing some book events and the band came to help me out. So I booked this tiny boutique hotel and did a doubletake as I was looking out my window. I am looking down on Jack's former apartment that we would crash in. Out of all the places we could have booked, here we are in the exact neighbourhood where it all started. Mind you the neighbourhood has changed a lot... with Whole Foods and fancy shops.

Jack was that guy who stood out front of gigs /clubs with his mimeograph-stapled little fanzine that he wrote every word of. Now it is a glossy, true magazine. It is the Bible of Independent Rock. God bless him.

Scene Point Blank: Yes, it is only out quarterly. I have only been to New York a few times but it has changed a lot over the years. I guess that is the life of a large city.

Mike Magrann: Well, especially like the East Village because, back in the day, it was truly deadly to the point that they said, you know, walk three blocks that way they will kill you for your shoes, dude. Now people are walking their French bulldogs at 3am on the way to get a coffee. So, for better or worse, each city transforms like that. It sure was a lot of fun when you were a kid. It was just like LA like on the weekends and after dark. All the people just abandoned the inner cities and that just left it wide open to the punk rockers and the wild men. It was just like those apocalyptic movies where you could run wild in the streets and there be no cop presence, no grown-ups. You basically could do what you wanted and we did, haha!

Scene Point Blank: Didn't you have gangs following bands in L.A. I think Suicidal Tendencies had attracted that crowd.

Mike Magrann:. Yeah, that was so stupid. In LA, when it fractioned off to gangs because I guess that was just a product of it being so huge out here. They do a Sunday matinee at the Olympic Auditorium out here and you get 5,000 kids and, when there were that many kids involved, of course it was going to splinter into neighbourhoods. I have never understood gangs at all -- or punks fighting punks.

It was just like those apocalyptic movies where you could run wild in the streets and there be no cop presence, no grown-ups. You basically could do what you wanted and we did.

Scene Point Blank: You had that band Circle One

Mike Magrann: Oh, yeah, Big John Macias, who was 6’5” and just ripped, you know. [The] dude had people following him and doing whatever he said, and he was just a scary motherfucker! I don't know if they were ever a gang. They started and finished the argument right then and there. Famously he was gunned down by the police on Santa Monica Pier for not complying with what he was being chased for. A fitting honorable, crazy death as well.

Scene Point Blank: We had a skinhead problem in the ‘80s in Toronto. I ate a steel toe boot. Suddenly they just disappeared or went underground but they were a form of a gang.

I’m interested in when Channel 3 recorded at Gold Star Studio with Stan Ross. Can you elaborate more about your experience?

Mike Magrann: Yeah, that was crazy that we got a chance to go in there. It was indeed that same old studio where Brian Wilson did all that crazy Pet Sounds stuff and Frank Sinatra would do his thing. It was just like a cathedral to us. That is another thing that changed -- as kids have this technology now on their Macbooks -- you can sit in your bedroom and record a whole album virtually over a weekend and, not only that, but with the internet, you can release your record. So it was a bit different back when you had somebody taking two hours in a studio to record a song which would cost maybe back then about $125 an hour. You had to have your song so together and you couldn't be wasting any time screwing around. The process was slow in choosing worthy songs and you had to practice until you had them just dead-on…and then the anticipation of getting it pressed. That's something that is missing from the new generation's accessibility. So for us, it was always just a thrill to go into those studios.

Scene Point Blank: I ask this question often and I usually get the same answer. Are you a digital guy or an analog guy?

Mike Magrann: You know, we still go into the studio whenever we have something to do. But as far as using tape, that went out a long time ago. On our Dr. Strange comeback record, we used tape and then, by the time you get done with it, it's all mixed down to digital anyway. Technology is pretty good with Pro Logic and all that, but we always prefer going into the studio and paying by the hour to do something because it just feels right.

Scene Point Blank: I was talking to a guy named Sonny Vincent, who stated that he puts it on tape and then makes it digital to edit, etc. Just like when they are now pressing records, they're like, hey, this is on vinyl and it's $50, however you can buy the CD for $10. It's just a digital file pressed on vinyl. I think the process of mastering vinyl is a dying art. I’m not sure there are many left who do this.

I was looking at the names that were recorded at Gold Star, names like Eddy Cochran, Ike and Tina Turner, and Ramones and so much more. So for you guys, it must have been like walking into the Beatles’ Abbey Road Studios.

Mike Magrann: What's interesting about living in Los Angeles or southern California is that you're privy to stuff like this -- and not just recording studios, stuff like the movie studios. We drive by Paramount Studios every day on Melrose. You don't think about it at all, although tourists are like, “Oh my god, is that the movie studio?”

The ballrooms out here were abandoned, and that's another thing that when punk rock came in and somebody said, “Hey, I'll give this guy $1,000 to use this ballroom for the night and put on a one-off punk show -- we're playing!” These fantastic movie palaces of the ‘40s were just shattered. I'd always walk through and look at the Art Deco decoration, the sconces and all that. Going into all these rooms with a bit of history was always just a kick!

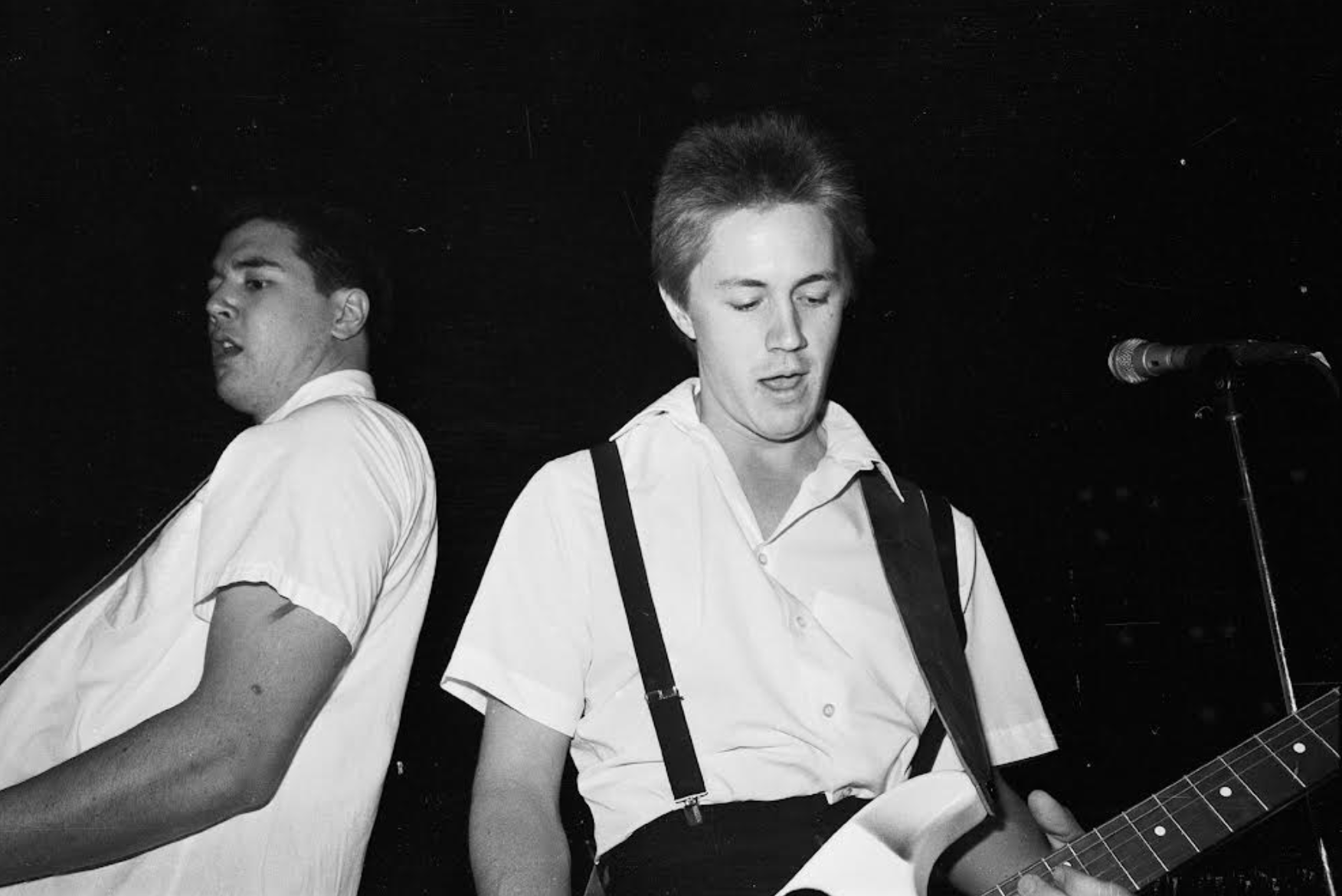

Scene Point Blank: When you first formed and were getting into music, you stated in the book you were listening to a lot of your brother's 45s or AM radio. When did punk first start rearing its ugly head and come into your sights?

Mike Magrann: I was born in 1960, so the punk scene didn't even come up until I was in high school. At the very start, there was some weirdness on the fringes like The Rocky Horror Picture Show. It ran at The Roxy for years when we were kids. Fringe rock 'n' roll stuff started happening and then you'd see of these bands pop up. If you went to clubs, few bands would have original material back then. Most of the bands were playing covers, so original bands would be a little rougher around the edges. That is around the time we would see Van Halen at The Whiskey. I think The Mumps were the opening band because they just couldn't find any other original band, so it was like, “What the hell is this,” you know? Growing up, the ‘70s were ruled by the major corporate rock acts or AM radio. My brothers were into Zappa and Beefheart and all that kind of weird stuff. So I think that probably moulded me to be open-minded towards whatever was coming. Then, in the mid-‘70s, it was labelled as punk rock and we were right there.

Scene Point Blank: It took the world a long time to catch up to punk, I think because when I was buying punk records, I was buying them very cheaply. Nobody wanted them and I was amassing records as a kid. I could buy five punk records or one Neil Young record, haha.

Mike Magrann: Well, this was pre-internet, pre-cable, pre-MTV, etc.

It takes so long for things to bleed from the coasts to middle America, so we probably already moved off from punk when it was hitting big in somewhere like Nebraska. Nowadays anything culturally significant is instantaneously transmitted across the country. So is that better, or is it worse? I don't know.

Scene Point Blank: I guess it has its merits now, as it can reach a wider audience quicker, but I like that word-of-mouth stuff that used to happen. “Oh, do you like Channel Three? Well, hey, check out this band,” or go into record ses and get educated by the disgruntled music snob behind the counter, haha.

Mike Magrann: How many records do you think that you had no intention of going there to buy and you just talked to somebody at the record store and walked out with an additional five records? I think that experience might not exist for kids today. I hope not though. Record stores were an important hub or community.

Scene Point Blank: I drag my family into record stores when we travel. My one son recently got into the Beatles when he was living in Liverpool. It was nice to see him discover the history and their music.

Mike Magrann: That's cool, seeing your kids develop their taste in music. I've got a daughter and she's 29 now, but when she was in her teens, she was right into Miley Cyrus and the boy bands and all that stuff. As she got a bit older she started buying her music on iTunes when it cost $0.99 a song. I looked at the purchases because we let her buy whatever music she wanted. I was like, “Did somebody buy London Calling on iTunes?” and she said, “Yeah, have you heard this?” I'm like, “There are four different copies of London Calling in this house.” Kids need to discover the likes of Led Zeppelin on their own as it's like discovering electricity!

Scene Point Blank: It's funny because I've never been a huge fan of Zeppelin. I love elements of Led Zeppelin and I did see Robert Plant with Alison Kraus once, but I was always more of a Sabbath guy.

Mike Magrann: I was going to say the same thing. I was more of a Sabbath or Who guy as well.

Scene Point Blank: I'm not a literary type, so I don't want you to think I'm some highbrow type guy. I don't mean to toot your horn or anything, but your book is very well written. I like how you tie it back and forth in time into the storyline. It made for a fascinating read and wasn't just linear.

Mike Magrann: Thank you. Yeah, I thought that if I did it chronologically it would be like I was born here and it's gonna end here. To me, that was a bit boring; however, that is how someone would naturally speak in telling a story. I am a punk rock guy so I wanted to shake it up a bit. I wanted to keep it interesting for the reader so, yes, going back and forth in time made sense to me. It is a book about the experiences of youth. I never stated that Channel 3 deserves a book. However, I did think it was a different story of friends who were just big fans of music that somehow became a band themselves. That story seems to register with people. We were not the most famous band, or groundbreaking, for that matter. We were just a reliable band that worked hard and have had a friendship that has lasted for all these years. Essentially that is the story,

Scene Point Blank: Were all the other band members on board with you writing this. Did you even have to check in with them?

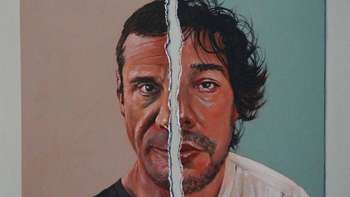

Mike Magrann: Really the band is just Kimm and me now. We've been through a million people since then. Jack was only the drummer for that one season, but I did reach out to everybody individually telling them I'm going to write about that one summer and you'll just have to trust me that I'm not going throw anybody under the bus or say scandalous stuff. I was willing to change names if people wanted to. Everyone said it was fine and everyone's been pretty happy with the outcome. Kimm thinks it was a little surreal to be reading it because I wrote it more as a novel than as a straight biography or memoir. Kimm thought it was weird to read a book where he was a character in the book.

Scene Point Blank: I think you stated that you fictionalized some situations, like taking a situation that happened a couple of years later but made it a part of the 1982 tour.

Mike Magrann: Yes, that is why I put a disclaimer in there and stated that this is not historically correct and I combined some stories from different tours. It does stay fairly true to the fact that these situations did occur. However, I did create some of those scenes to give a feeling of what it was actually like to be living in a van and playing all these different shows on the road. I thought it was more interesting than just saying we played here on this date and on this date we played in this other city. I'm more interested in what it felt like to be in Georgia in the middle of summertime touring the country in a hot van filled with beer cans.

Scene Point Blank: So it is more of a story than a straight-up biography or a snippet in time? How did you get involved with DiWulf publishing?

Mike Magrann: When I was done with the book I knew some published writers so I sent them some excerpts. They came back with, “This is more of a book than a punk rock thing.” Their suggestion was to get it published by a regular publisher. That was just a dead end. I spent a couple of months just trying to get an agent. Not a single person at a regular publishing company would take a look at it. So, I looked to the punk rock community and spoke to Jerry A. Lang from Poison Idea and Brad Logan from Leftover Crack to ask them for their contacts and or who they used for their publishers. However, I soon found out because of COVID-19 that all these people had extreme backlogs and wouldn't even be able to talk to me until 2025. I was ready to write my next book. The fun of writing a book was in the art and creation of the book and story but, all the post-production and printing, I had no interest in at all. I was antsy to get the show on the road. I then spoke to Dave Scott Schwartzman of Adrenalin OD and he gave me the contact at DiWulf Publishing. I sent an excerpt and he thought this would be an interesting project. So we spoke on the phone and started the process of editing back and forth through email. It surprisingly went very quickly. I believe that process took about 6 months. They printed some proof copies and then it came out. It has been a great relationship. I have done some release events for the book as well. Hopefully they are happy with the end result.

Scene Point Blank: How long did the book take you to write in totality?

Mike Magrann: I wrote the book in about nine months. I put my mind to it to keep on schedule. I can be a great procrastinator and lazy at times, so I said to myself: I have to write a chapter every ten days. I had it in my mind it would be 19 chapters. It grew to 140,000 words. It was hopelessly too big, so I put it away for a few months and then took it out again and paired it down to 90,000 words. The writing was not a torturous process however the editing was a lot more involved than I imagined.

The book itself is a story, one summer in a character's life. It allowed me to get back into the past and reflect on things. The story had to be who was in the band, what the music meant to them, and how it impacted the rest of their lives. The small stories and the stories of the characters. Those are more compelling to me than the dynamic plot. Some stories involve gunshots and fires -- but that is an action movie. If you talk about one man's travels through one summer -- life-changing experiences through music -- now that is a great story, in my opinion.